Catalog II

The exhibition „Dialogue“ by Willie Bester and Wolf Werdigier, opened on February 1, 2025, and run until February 28, 2025, at the „Art B“ Gallery in Belleville, Cape Town.

https://www.artb.co.za/dialogue-intro/

This exhibition provided the framework for a discussion that spanned several phases.

Phase 1

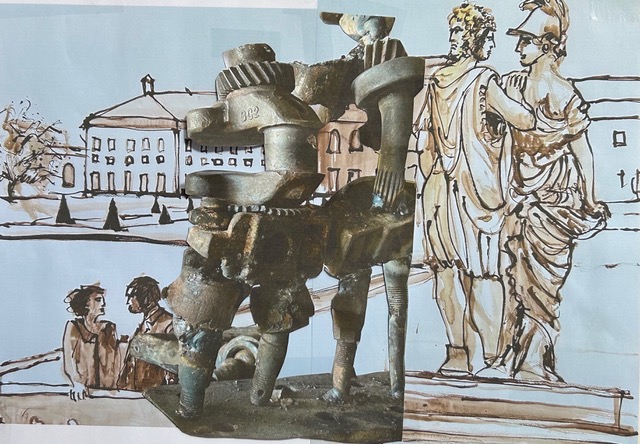

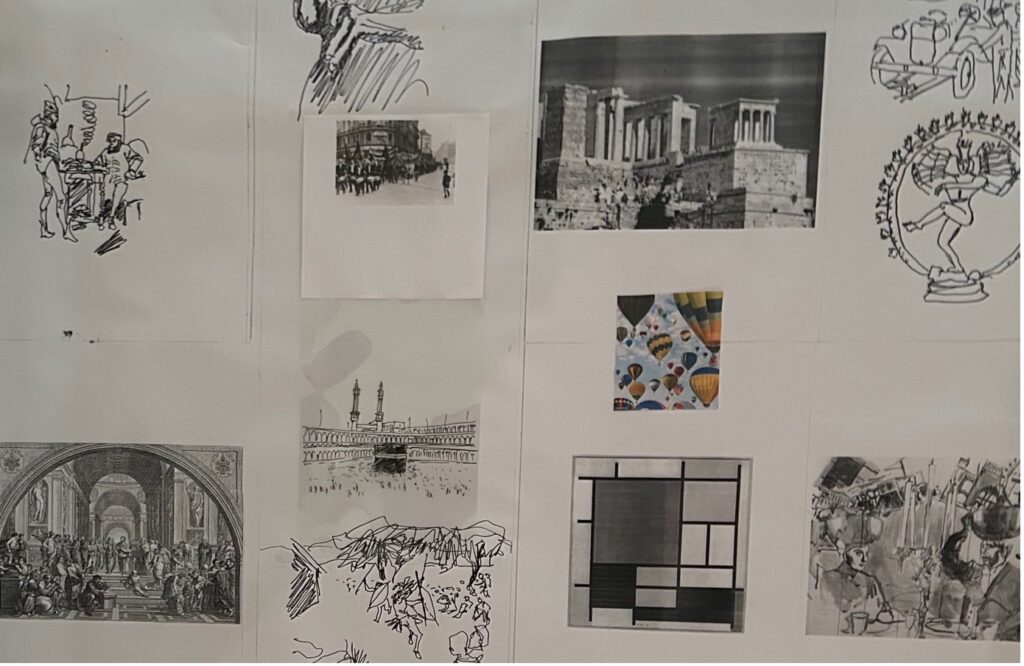

While the first phase, the exhibition itself, focused on the dialogue between the two artists, the theme was how the art of Europe (Wolf Werdigier) and the art of Africa (Willie Bester) relate to and influence each other. It also represented a years-long dialogue between two artists about history and the traumas in their history, Apartheid and Holocaust. And it also represents the development of a long-standing friendship between the two.

The exhibition includes more than 70 works of art, paintings, and sculptures by both artists. The large space in the „Art B“ gallery provided the opportunity to represent the idea of dialogue in the exhibition’s architecture.

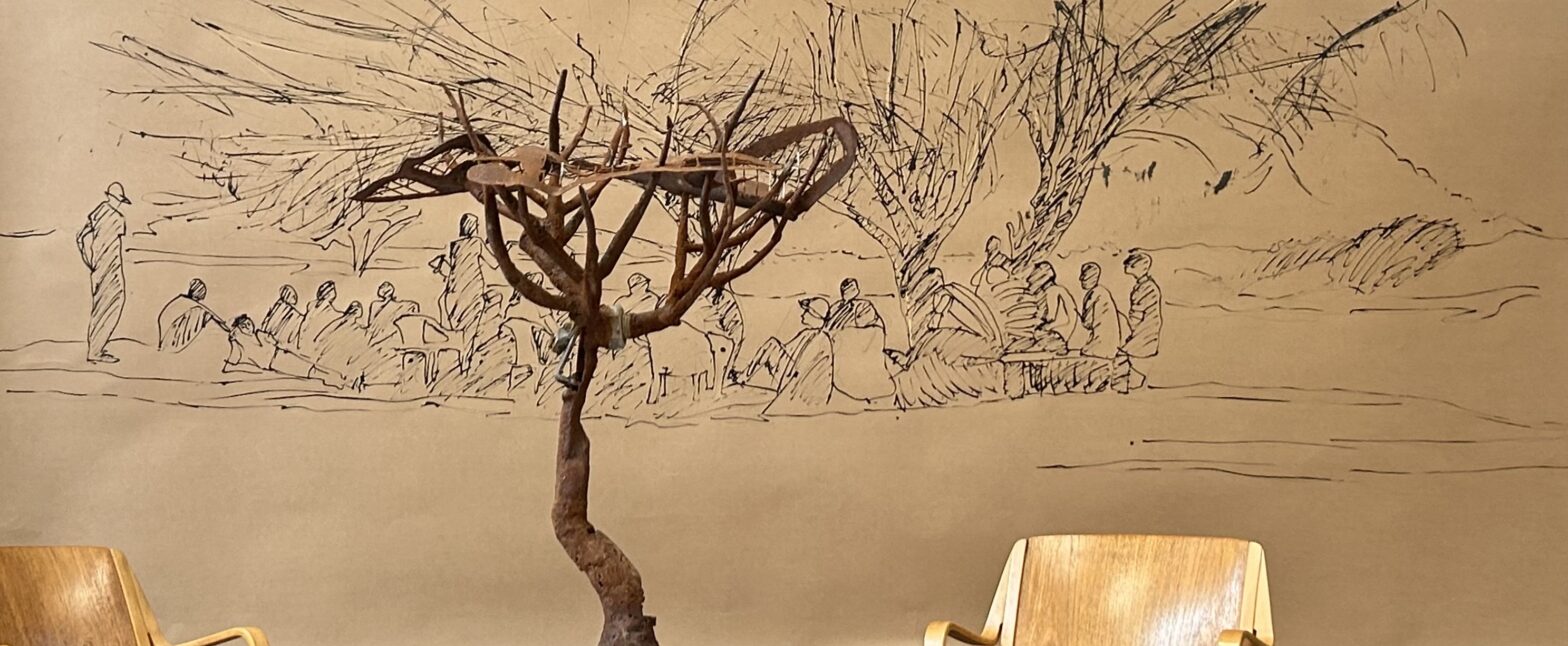

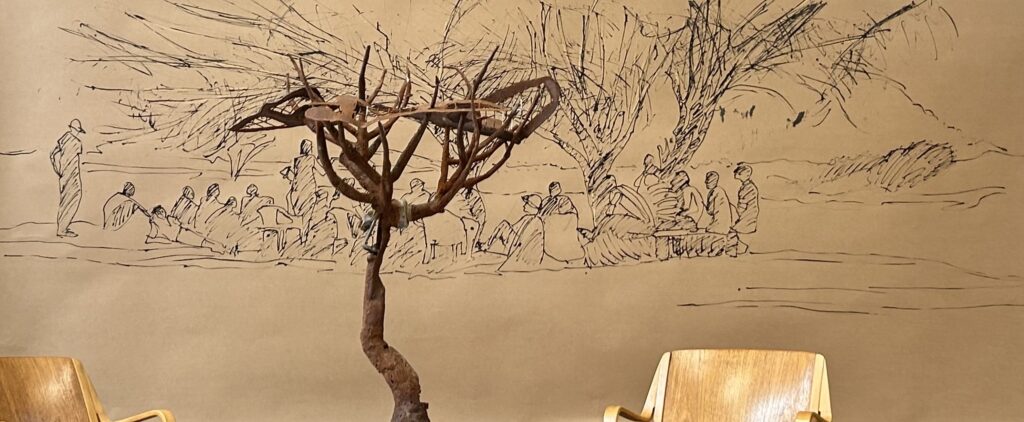

From a European perspective, the Greek Agora, and the associated Stoa as a promenade, are a classic representation of dialogue. The Stoa was adorned with numerous sculptures along which people used to walk.

When asked what the appropriate motif of dialogue in Africa would be, the answer came: the tree under which people gather to talk. Willie Bester immediately provided the sculpture of his tree to accompany the corresponding drawing.

Phase 2

In the second phase, during the preparations for the panel discussion on February 15, 2025, with Marlene le Roux, Regina Isaacs, Philip Todres, George Hull, Willie Bester, and Wolf Werdigier, Willie Bester in particular expressed concern that South African society was dividing into different bubbles based on its ethnic groups, with one group having little understanding, often not even knowledge, of the history and traumas of the other. This led to a further development of the term „dialogue“ into a desire to open dialogue between these „bubbles.“ This also occurred in a very emotional way during the open discussion on February 15.

Phase 3

In phase three, further discussions in a smaller group led to a further in-depth discussion of the topic:

George Hull provided his association with a hall of mirrors in a written contribution:

“I still feel there is potential in the hall of mirrors as a visual concept. In a nutshell, South Africa is a complex society marked by multiple different lines of conflict, difference and oppression, and each person who becomes self-aware wakes up each day and enters a hall of mirrors in terms of how they are aware of being perceived by diverse other individuals, some of the reflections very distortive, some reflecting multiple personae which they really embody. This experience in itself can be overwhelming or harmful, though for others it becomes a maze which they are adept at navigating, sometimes using it to control people’s perceptions of them (there are many Ripley figures in such a society).

My thought was that in South African history and in the present, there is a disanalogy with some other conflicts, including perhaps the Palestine-Israel conflict, because there has been so much contestation not just about the facts of the conflict, but about which groups are actually in conflict. Is it for example:

- All black groups and Afrikaners vs. their common colonizer, the British?

- Each separate nation, Indian, Coloured, African (maybe also Thembu, Zulu, Mpondo, Tswana,…), white (maybe also Boer and Brit) in need of its distinct cultural renaissance and national apotheosis?

- All black groups vs. their common oppressor—the white people?

- The working-class toilers, white or black, vs. the capitalist owners and their divide and conquer tactics?

- Those of all groups who have embraced a „rainbow nation“ democratic mentality vs. those still stuck in divisive and racist mentalities from the past?

- True South Africans vs. foreigners (however defined)?

All of these have been brought to the fore as salient divisions both during the struggle and since the coming of democracy. This makes it hard to say in South Africa: these are the two sides, now let’s ask them about their thinking.

Also, though there is much talk of people retreating into laagers, South Africans generally rub shoulders with many people from different backgrounds daily, and interact with them as colleagues, in commercial and domestic situations, on social occasions, see them voicing opinions on TV etc. South Africa is a highly urbanized country and today it is not really a country of groups separated and isolated from one another. With each generation, the de facto social segregation has reduced markedly since the 1980s.

My suggestion was that coming to self-awareness in South African society involves being sensitive to and being able to manage the multiple ways you may be perceived by others at any given time. For example, I was once giving a lecture on democracy and was addressing the question of whether minority opinions should have certain protections from the will of the majority; at a certain point, from the questions I realized I was being interpreted as talking about the opinions of minority racial groups, whereas I meant minority opinions which might be held by people of any race. When I am giving a lecture about affirmative action, I know I will be simultaneously perceived by some people as a bleeding-heart liberal trying to be politically correct, and by others as a white person who just doesn’t understand the extent of the problem and is out of touch. If I say things about religion in a lecture, meaning it to apply to all supernatural beliefs, sometimes I realize some students think ‚culture’—traditional African religious practices—are something different from religion and so what I am saying doesn’t apply to them. If I mention ‚liberalism‘ in a lecture, to some students this is a political ideology which they think is too tolerant, to other students it is the name for a patronising attitude of white people in the past. My thought is that one has to come to terms with the multitude of different impressions one is making at all times, and somehow anticipate them or manage them without letting it overwhelm you. That is why a hall of mirrors seems to me an apt metaphor, because the secret is not to get too fixated on one reflection or be paralysed and unable to move forward—you have to take the distorted reflections of you in your stride. And of course you have to be open to the fact that your perception of another may well be a distortive reflection!

Some people deliberately play with perceptions, such as highly educated Africans who may nonetheless dress in overalls as though they are construction workers (for example, a few lecturers at UCT do this, and the EFF does it in Parliament) to trick people into seeing them as working class and then exposing their assumption. Some African South Africans are frighteningly adept at taking on a different persona in rural settings with their extended family and in the city when studying or working. There are some people who work in corporate jobs but are also traditional healers (sangomas): they will alter their dress to suit the different roles. So in many ways South Africa is a society where one person can have not just multiple different reflections but multiple personae.

So trauma does come into it, because as we discussed people can fixate on a particular reflection of others or themselves which is one-sided, and that leads to the behaviour which is off balance and insensitive. But my feeling was that there might be enormous potential in South African society for asking people to describe or depict „the different versions and the different perceptions of you“, and to think about why they are seen in these different ways by different people. I do think this also unlocks the door to experiences of trauma, because one often finds that someone had a particular experience with a white person or a black person or a person of a particular ethnicity which has now coloured all of their interactions with people of that group. Or one also sometimes hears people’s tremendous frustration that they keep being seen as something they’re not—whether this is a black person who is highly qualified but is assumed to be a menial worker, or a white person who is assumed to be racist, etc. Perhaps there is also the phenomenon of having to adopt so many different personae (especially in rural settings with extended family, vs. in the city where ones lives vs. in the city where one studies/works) that keeping so many balls in the air becomes traumatic itself.“

Around the same time, Daniel Herwitz completed his latest book, „Restorative Justice and the Problem of Offense,“ which explores the possibilities of reconciliatory approches. Normally, the rights of individual citizens in a democratic society are legally protected and enforceable. Both in societies where historical conflicts have traumatized individual groups, e.g., Apartheid in South Africa, the Holocaust in Europe, African Americans, etc., but also today in societies where personal humiliation and insults become part of the political language, e.g., right-wing extremist parties in Europe, or Donald Trump in the USA, restorative justice methods are necessary to achieve reconciliation or at least understanding before the courts begin to prosecute the issue. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission was such a large-scale process, but it also became clear in the emotional and honest discussion at the exhibition on February 15 that statements about the traumas suffered by Afrikaners at the hands of the English in 1901 could not simply be discussed alongside the traumas suffered by Black Southafricans.

This necessary confrontation is reminiscent of the „Hidden Images“ project, which I conducted in Israel and the occupied territories in 2006:

In his 2014 book „Tales of the Metric System,“ Imraan Coovadia described South African society based on ten fates between 1970 and 2010, based on the respective historical situations. People who were exposed to specific constraints due to their ethnicity and due to the times in which they lived:

In 1973, someone suddenly becomes a criminal because he lost his passport; in 1985, you may witness an act of treason in London; in 1990, a young Black man in a township is suspected of being an informer and hunted down. Set in 1995 during the Rugby World Cup and the TRC; in 2003, someone is forced to die because HIV was officially denied; and in 1976, children die in the Soweto uprising.

Phase 4

Further perspective: In artistic terms, dialogue also means confrontation. If one seeks the original strength of African art, one could say that it can most prominently be found in fashion, namely in Africa itself, in African American fashion design, as well as among Black fashion designers in England.

This leads back to the beginning of the exhibition:

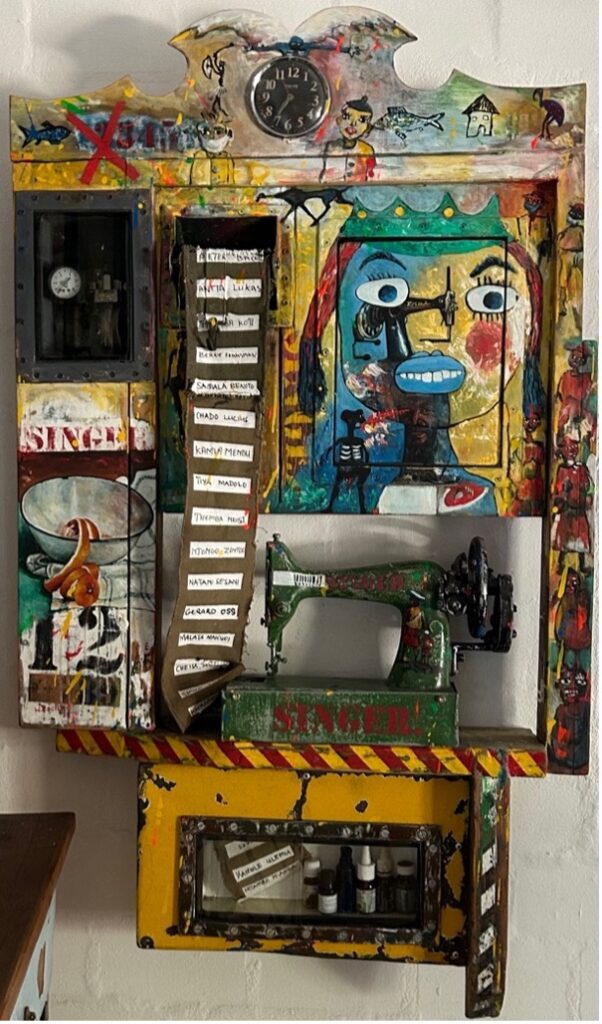

Albie Sachs, gave the opening speech. At the end of his speech, he emphasized the meaning of “Singer”, as represented in a work of Willie Bester. He spoke about the importance of sewing for African women throughout history: making their own clothes, being able to earn money by sewing, but also organizing themselves into unions as seamstresses, with the unions playing a significant role in the overthrow of the apartheid regime. This historical significance of the name „Singer“ is a foundation that continues to this day and can perhaps be described as a kind of myth of African art.

If we look at a tableau that combines the developments in African fashion design today with the sculptures in the exhibition, and also connects these with fashion designs from Dadaism and the Bauhaus, we find a revue of the development of influences and forms, as if they were all belonging to each other.